The Aztec Empire flourished in the Valley of Mexico between A.D. 1325 and 1519 and was the last great civilization before the arrival of the Spanish in the early 16th century.

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

A modern ceramic reproduction of the Aztec calendar stone known as the Stone of the Sun. The original, carved in basalt, was excavated in Mexico City in 1790. The stone has become an informal national symbol of Mexico. (Image credit: RapidEye via Getty Images)

The Aztec Empire flourished in central Mexico during the Postclassic period of Mesoamerican history, from approximately A.D. 1325 to 1521. It is considered one of the great civilizations of the Americas — known for amazing feats of urban planning, engineering, military conquest and unique artistic innovations — and the last great Mesoamerican civilization before the arrival of the Spanish in the sixteenth century.

The Aztecs, also known as the Mexica, ruled by a combination of fear, skillful political manipulation, alliances and military force. At the same time, the Aztecs were renowned artisans, engineers, builders, traders and agriculturalists. They created colorful and intricate art, vast cities with towering pyramids and great aqueducts, a highly productive agricultural system and a writing system that made use of logograms and syllabic signs.

Today, the influence of the Aztecs on modern Mexican society and culture is profound and far-reaching and can be seen in cuisine, architecture, art, literature and more.

According to legend, the Aztecs migrated into the Valley of Mexico from Aztlán, reputed to be somewhere in the North. (The word "aztlán” is from the Nahuatl language and is typically translated as "white land," or "land of white herons," according to Britannica.) These migrants were likely hunter-gatherers from northwest Mexico who were organized into a loose confederation of nomadic tribes, according to Britannica; they were skilled hunters and warriors who were openly hostile to the settled inhabitants of the Valley of Mexico.

As depicted in several Aztec codices, the famous Indigenous manuscripts written on bark paper and folded like an accordion, the Aztecs were led to the Valley of Mexico by their chief god, Huitzilopochtli, according to New World Encyclopedia. Much of the valley was already inhabited, including the good agricultural land, so the Aztecs settled on an island at the western end of Lake Texcoco. They built their capital city, Tenochtitlán (modern-day Mexico City), on the spot where they observed an eagle — a potent symbol in Aztec ideology — perched atop a nopal cactus and clutching a snake in its talons (an image depicted on the modern Mexican flag).

Modern archaeology, however, paints a different picture of Aztec origins. The people who would later be known as the Aztecs were one of many Nahuatl-speaking groups occupying the Valley of Mexico. During the 12th century A.D., many of these peoples began to organize themselves into independent communities. "The basic political form of these groups was the city-state," Michael Smith, a professor of archaeology at Arizona State University (ASU) and the director of the Teotihuacan Research Laboratory at ASU, told Live Science.

In Nahuatl, "city-state" is translated as "altepetl," and much like the city-states of ancient Greece, for example, the city-states in the Valley of Mexico were independent political entities with their own standing armies, Indigenous identities, and political and religious structures. Like Athens, the Aztec city-state of Tenochtitlán grew from obscurity to military and political prominence through a gradual program of alliance and military dominance, Smith said.

At first, as legend has it, the Aztecs eked out a precarious existence on their island, practicing agriculture and building a small settlement that gradually expanded. Fierce warriors, they often battled with the other peoples of the region. Other times, they hired themselves out as mercenaries in the many wars in which the inhabitants of the valley were engaged. Either by force of arms, alliance or skillful politicking — or a combination of all three — the Aztecs gradually came to dominate the surrounding tribes and city-states in the region, according to World History Encyclopedia. It is possible that the Aztecs contributed to the downfall of the Toltecs, who were the dominant political and cultural force in the Valley of Mexico before the rise of the Aztecs, according to World History Encyclopedia.

In 1427, the Tepanec War — a conflict that pitted the Aztecs against the Tepanecs of the city of Azcapotzalco — broke out. It was precipitated by a civil war that flared up between two Tepanec rulers who vied for power after the death of the Tepanec king, Tezozomoc, according to Omni Atlas. The Aztecs sided with one of the claimants, a man named Tayahuah, who opposed Tezozomoc's son, Maxtla. Initially, the war went poorly for the Aztecs; the Aztec ruler, a man named Chimalpopoca, was killed in the conflict. But, with the ascension of the new Aztec ruler, Itzcóatl (who ruled from 1428 to 1440), the war took a dramatic turn. Itzcóatl, in a coalition with several city-states, marched on Azcapotzalco, overthrew Maxtla and captured the city.

Soon thereafter, in 1428, Itzcóatl formed an alliance with the neighboring states of Texcoco and Tlacopan, two of the more powerful city-states in the region, according to World History Encyclopedia. This came to be known as the Triple Alliance and is viewed by some scholars and archaeologists as the beginning of the Aztec Empire (other scholars argue that the empire began much earlier in 1325, which is the date of the founding of Tenochtitlán). At first, the three cities ruled the valley relatively equally. But gradually, the Aztecs gained sole political power and hegemony of the region.

"The Aztecs ruled by a policy known as 'indirect control,'" said Smith, which is a form of political control, as opposed to 'direct control,' that does not intervene directly in the political, cultural or religious institutions of the conquered group. As long as the province or territory paid the necessary taxes it owed the Aztec Empire in full and on time, the Aztecs left the local leaders alone, Smith explained.

During the reign of Moctezuma I, from 1440 to 1469, the Aztecs extended their borders southward to the Valley of Oaxaca, westward to the Pacific, and eastward to the Gulf of Mexico. Moctezuma also carried out a successful war with the Mixtec peoples of southern Mexico. With these new regions added to the empire, trade goods, tribute and taxes began to flow into the city of Tenochtitlán. These goods included shells from both coasts, jade, parrot feathers and feline pelts from the tropical forests of the south, as well as precious stones and metals, such as gold and silver, from all over the empire.

"The Aztec Empire grew little by little as each ruler enlarged Aztec territory through time by conquest and alliance," said Laura Filloy Nadal, associate curator for the arts of the ancient Americas at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. "The goal of this conquest was not only to gain territory but also to gain access to materials and goods from around Mesoamerica."

Ahuitzotl, who ruled from 1486 to 1502, was the grandson of Moctezuma I and a hugely successful military leader. He launched the most ambitious military campaigns of any of his predecessors, adding large swathes of land to the empire, including land as far south as what is now the southern border of Mexico and Guatemala. He carried out successful military campaigns against several Mesoamerican peoples, including the Huastecs and Zapotecs. He was also an ambitious builder who added buildings, temples and palaces to Tenochtitlán; refurbished the massive Templo Mayor; and developed a far-flung network of roads that connected the empire from coast to coast and from north to south.

Ahuitzotl is also famous for promoting the Aztec practice of ritual sacrifice. Human sacrifice had existed as an integral part of Aztec culture for a long time, but Ahuitzotl raised the practice to unimagined heights, often sacrificing captives captured in war in the temple of Huitzilopochtli. According to Britannica, Ahuitzotl sacrificed some 20,000 captives during the festivities surrounding the dedication of a new temple in Tenochtitlán in 1487.

The Aztecs sustained and consolidated their empire through an extensive system of taxation. This was not simply tribute, or a one-time payment, Smith said. "The Aztecs had a regular, sophisticated system of taxation that was comparable to what the Romans and Greeks were doing," he said. Cocoa beans and cotton textiles, which were the Mesoamerican forms of currency, were the primary forms of taxes that subordinate people paid to their Aztec overlords, Smith added. Cocoa beans were used for small monetary transactions, while cotton textiles were used for larger transactions.

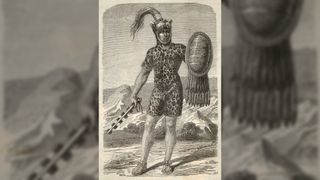

The Aztecs maintained their empire — and fended off rival societies — through a highly effective, well-trained military. All Aztec boys were trained from an early age for war in special military compounds, according to World History Encyclopedia. The ones that showed particular promise were inducted into the military, where they at first assisted the other warriors by carrying weapons and supplies and occasionally acting as skirmish troops. It was only later that these young warriors were allowed to fight in hand-to-hand combat. One of the main goals of Aztec warfare was the capture of sacrificial victims; in fact, an Aztec fighter was deemed successful and acquired status by the number of warriors he could capture in battle, and whole wars — known as the Flower Wars — were fought with neighboring groups for the sole purpose of capturing enemy warriors. A warrior who captured 20 captives was allowed to join the elite fighting units of the Aztec army, such as the jaguar and eagle units.

By the early 16th century, the Aztec Empire was at the height of its power. The Aztec state was well organized, with a complex bureaucratic system that included governors, soldiers, law courts, tax collectors, and civil and religious officials. At the top of this hierarchical pyramid was the monarch, called the "tlatoani" in Nahuatl. The monarch ruled over some 5 million to 6 million people spread over 80,000 square miles (207,200 square kilometers), according to Britannica. This vast area contained about 400 to 500 city-states.

Today, Tenochtitlán is buried under modern-day Mexico City. Some 500 years ago, however, the Aztec capital was a thriving metropolis of approximately 400,000 inhabitants, which made it larger than most major European cities of the same time period. Laid out with razor-straight avenues and broad causeways that connected the city with the lakeshore, Tenochtitlán was a city with pyramids, temples, palaces, artificial reservoirs for fresh water, and gardens. There was even a great aqueduct that carried water from the distant Sierra Madre mountains directly to the city. The Aztecs fed the inhabitants of the city via a sophisticated agricultural system made up of "chinampas," or "floating gardens," which were artificial islands made by adding successive layers of mud, sticks and vegetation until a small island was formed. These chinampas were highly productive and sustainable, according to 2020 research in the journal HortTechnology.

In the center of the city was an area known as the Sacred Precinct, which contained the gods' temples and a monumental ball court, according to World History Encyclopedia. The most prominent temple in the Sacred Precinct was Templo Mayor, or the "Great Temple." This towering pyramid, which dominated the city's skyline, was crowned by two temples: one dedicated to Huitzilopochtli and the other to the rain god Tlaloc. Two parallel staircases, each flanked by large snake heads carved in basalt, led up the pyramid from ground level.

According to Nadal, Templo Mayor measured 256 feet (78 meters) at its base from north to south and 274.3 feet (83.6 m) from east to west. Its height was 148 feet (45 m), a length comparable to the Pyramid of the Moon, the second largest pyramid in Mesoamerica, which is located in the pre-Hispanic city of Teotihuacan, located just east of modern-day Mexico City. The materials used in the construction of Templo Mayor included igneous stone, earth, limestone, sand and wood, Nadal said.

Although Templo Mayor was discovered in 1914, it wasn't extensively excavated until 1978, when Mexican archaeologist Eduardo Matos Moctezuma and his colleagues completely uncovered the pyramid from the rubble that had covered it for centuries, Nadal said. They discovered that, although the initial construction of the structure began in 1325, the temple was renovated at least six times over the centuries, reaching its final form just before Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés arrived in 1519.

The Aztecs were polytheists — that is, they propitiated a panoply of gods, each with different powers, temperaments and symbols. By some estimates, no fewer than 200 gods constituted the Aztec pantheon, according to ThoughtCo. There were four major gods and a multitude of minor gods. The chief god of the Aztec pantheon was Huitzilopochtli, a war god whose name is translated as either "left-handed hummingbird" or "hummingbird of the south," according to Britannica. He is associated with the sun and fire, and often depicted as a warrior decked out in colorful hummingbird feathers and carrying a shield in one hand and a snake in the other. The lower part of his face is typically blue, while the upper part is black.

An equally important Aztec deity was Quetzalcoatl, whose name means "feathered serpent." He was the god of light, wisdom and the arts, and was associated with the wind and the planet Venus. In Aztec culture, he gave several gifts to humankind — including books (codices), the calendar and maize (corn) — and, in some depictions, was opposed to the practice of human sacrifice. Some of the earliest mentions of Quetzalcoatl come from the pre-Hispanic site of Teotihuacan, where feathered serpent motifs are prevalent in the art of the city. He was also worshipped by the Maya of the Yucatán, who knew him as Kukulcan (also spelled Kukulkan).

Tezcatlipoca, which means "smoking mirror," is the Aztec god of judgment, the Earth, divination, sorcery and the night. Although he is portrayed as the "invisible god," he is frequently depicted in Aztec art with black and yellow stripes painted across his face, heron feathers on his head, seashells on his wrists and ankles, and a colorful shield. He also carries an obsidian mirror that he uses to divine the future and see into humans' thoughts. He was also worshipped by other Mesoamerican societies, such as the Toltecs and the Maya.

The Aztecs also worshipped the rain god Tlaloc, whose name means "he who makes things sprout." He is often depicted in Mesoamerican art wearing a mask with protruding fangs, similar to a jaguar's. In addition to rain, Tlaloc is associated with agriculture, fertility and storms. He is one of the most ancient Mesoamerican gods, according to ThoughtCo., with depictions of Tlaloc appearing as early as the Olmec culture, which flourished in the modern Mexican states of Veracruz and Tabasco from 1200 B.C. to 400 B.C.

"By the time of Moctezuma II, in the early 16th century, the Aztec Empire was at its largest extent," Nadal said. "The Empire was divided into at least 61 provinces that covered what is today most of the central part of Mexico." In 1519, however, Cortés invaded the Aztec Empire. With 500 Spanish soldiers, he landed in Veracruz and proceeded to march inland, allying himself with several Indigenous groups that were at odds with Aztec rule, especially the Tlaxcalans, a Nahuatl-speaking people from Tlaxcala who fiercely resisted Aztec rule and whom the Aztecs had never succeeded in conquering.

When Cortés reached Tenochtitlán, he was in command of thousands of warriors, all intent on toppling the Aztec Empire and looting the city. The Aztecs, under their new ruler, Cuauhtémoc, at first put up a stiff resistance. But the superior iron weapons, arquebuses (matchlock rifles), cannons and cavalry of the Spanish as well as the hostile Tlaxcalans ultimately proved too much for the Aztecs. In 1521, Cortés and his allies succeeded in capturing the city.

But force of arms was not the only factor leading to the Aztecs' demise.

"European diseases, especially smallpox, played a decisive role in Cortés' victory," Smith said. "The Indigenous people simply had no immunity, and the disease ravaged the region — killing thousands."

According to Suzanne Alchon, a historian and author of the book "A Pest in the Land: New World Epidemics in a Global Perspective" (University of New Mexico Press, 2003), between one-quarter and one-half of the inhabitants of the Valley of Mexico, including the Aztecs and other Indigenous peoples, died of the disease.

Today, whether rightly or wrongly, the Aztecs are known in the popular imagination primarily as fierce warriors who engaged in blood-curdling human sacrifice. But they were so much more, Smith said: They created perhaps the most sophisticated civilization in Mesoamerica and engaged in massive engineering and building projects that rivaled and, in some instances, surpassed those being conducted in Europe at the same time. Aztec artisans created some of the most distinctive artwork in the Americas, and their wondrous stone, feather and ceramic pieces are now on display in museums around the world.

Originally published on Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.