In this post, I’ll give a summary for Great By Choice – a book by Jim Collins. I’ll outline:

Keep in mind that this book summary is just from my own lens of reading the book. It’s not a complete summary of the ideas in the book. If you’re in any sort of entrepreneurship, you’d greatly benefit from reading the book in full for yourself.

The book studies a lot of successful companies vs. a lot of companies that’s failed. It talks about 3 main patterns they’ve observed in the most successful companies. The rest of the article will focus on these 3 ideas.

This is the idea that consistent and disciplined action over time will always win when compared to overly aggressive action that’s unsustainable over a long period of time.

The author illustrates this with a thought experiment called the “20 Mile March.”

Imagine you’d like to march from the West Coast to the East Coast. And imagine you consistently march 20 miles a day. Some days will be easy. Some days will be hard. On days where you think you could do 40 miles, you do 20 miles. This conserves your energy so you an handle harsher days ahead. On days where the weather is bad, you think you can do 2 miles, but you force out the 20 miles so you don’t get too far behind. You keep this up and you end up in the East Coast in a fairly predictable amount of time.

Now imagine now you travel just ‘as much as you can.’ On average days, you travel 20 miles. But on those days that’s fairly easy and you think you can do 40 miles, you do the full 40 miles. You push yourself extremely hard on days where you feel good so that it saps your energy. Being drained all the time, you injure yourself eventually by being not attentive enough on the trail. You get delayed. In addition, on bad days, you go ‘as hard as you can,’ which is 2 miles. This makes you further delayed. In the end, you do things on a whim and you probably won’t make it to the East Coast. And if you do, it’ll be in a completely unpredictable timeframe.

This may seem like a contrived example, but getting injured by going “too hard” is a real phenomenon in athletic endeavors. And more importantly, this is exactly what happened in the case study of Stryker vs. another competitor.

Stryker’s goal was just to grow 20%, year over year. No more, no less. Their thinking is that they should be consistent in their growth: they shouldn’t be too lazy as to produce less than 20% growth per year, and they shouldn’t take so much risks that they could get more than 20% growth in any given year.

Their competitor would try and grow and dominate markets as quickly as possible. Their thinking is much more simple: why not get more profits if you can?

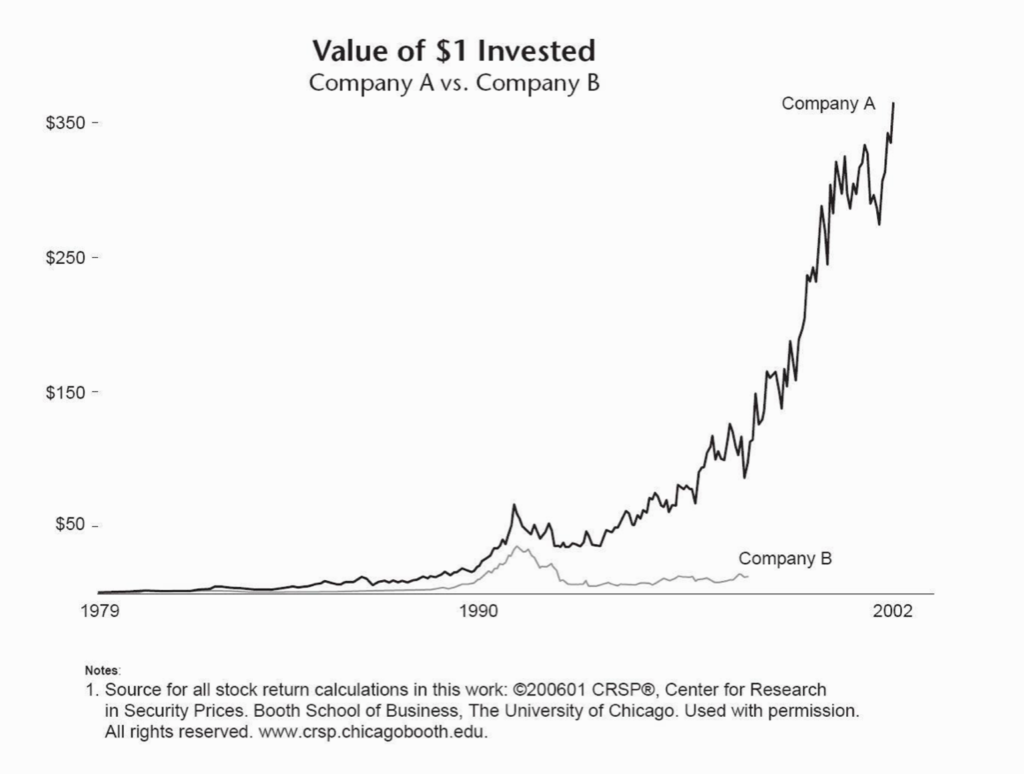

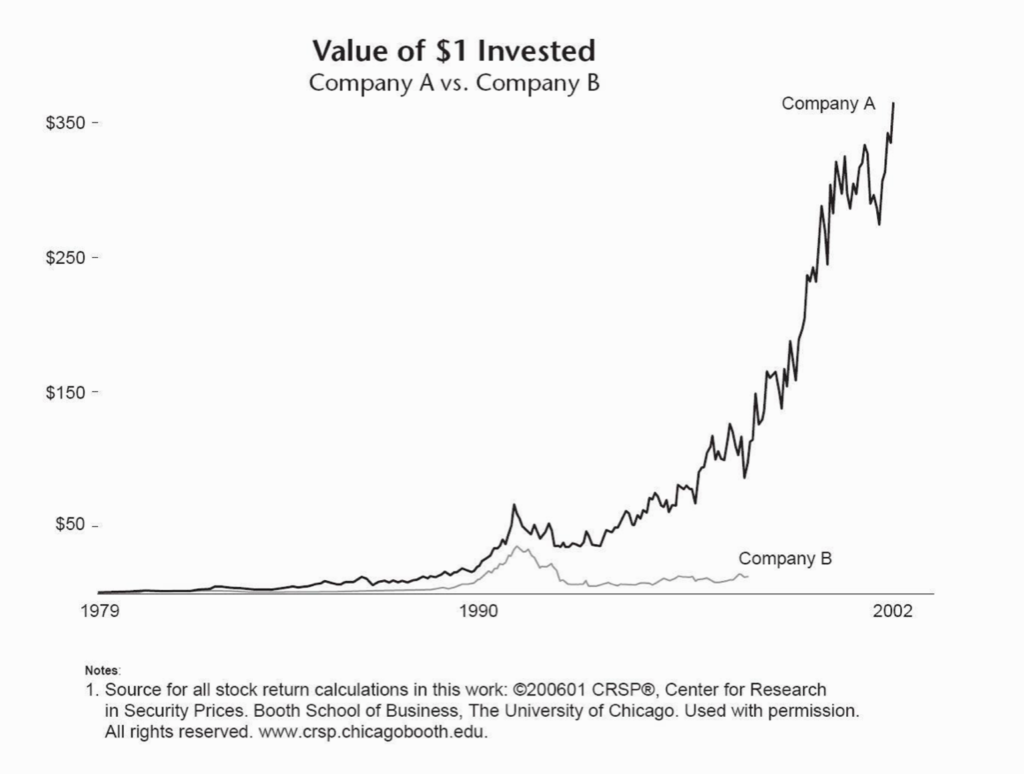

Here are the results of the 2 companies. Stryker is Company A listed below and the competitor is Company B.

Stryker’s competitor had years where they’d 300%+ and outdo Stryker. But they also had years where they’d lose a lot of money.

The graph doesn’t show this, but Stryker’s competitor enjoyed a 45% average annual growth in the same 19-year period that Stryker enjoyed only 25% growth.

Despite that, we can see that in the 1990s, Stryker’s competitor made some mistakes and never recovered. This is because their plan to expand was too aggressive, which caused them to make unnecessarily risky decisions. There are more specifics in the book, but basically when these risky decisions didn’t go their way, their company got severely damaged and was no longer able to recover.

Stryker, on the other hand, just grew slowly over time.

Stryker has extreme discipline and would only aim for a 20% growth YoY. If they had opportunities to pursue more, they wouldn’t take the risk to do so. And during bad years where 20% growth seemed out of reach, they’ll do everything they can do reach it.

In conclusion: you can try for a higher return if you’re willing to take more risks. In the context of running a company, taking more risks means you might hit a threshold of risk where if you screw up, you might never be able to recover again. Conversely, if you aimed for more modest growth, you only need to take moderate risks. If your risks don’t work out – you might lose money, but you’ll always be able to recover from it.

The next big idea in the book is productive paranoia. This is the idea that one should be paranoid about worst-case scenarios, and should take productive steps in minimizing/mitigating these scenarios.

The book has recurring stories about 2 expeditioners that wanted to be the first person to reach the South Pole. The first expedition is Amundsen, whose preparation and methodical approach parallel successful businesses. The 2 nd expeditioner is Scott, whose risk-tolerance, “innovative” approach, and lack of preparation parallel businesses that died – just like he did.

I’ll leave a ton of details out here for brevity. But in short, Amundsen prepared for his journey to the South Pole in this style:

“When setting supply depots, Amundsen not only flagged a primary depot, he placed 20 black pennants (easy to see against the white snow) in precise increments for miles on either side, giving himself a target more than ten kilometers wide in case he got slightly off course coming back in a storm. To accelerate segments of his return journey, he marked his path every quarter of a mile with packing-case remnants and every eight miles with black flags hoisted upon bamboo poles.”

Whereas Scott’s style of preparation reflected something like this:

“Scott, in contrast, put a single flag on his primary depot and left no markings on his path, leaving him exposed to catastrophe if he went even a bit off course”

Another example of Amundsen’s preparation:

“Amundsen brought four such thermometers to cover for accidents.”

Scott did not do the same:

“Scott brought one thermometer for a key altitude-measurement device… “and he exploded in “an outburst of wrath and consequence” when it broke”

If you know anything about business or ‘black swan events’ – you’ll know that worst-case scenarios aren’t a matter of if they’ll happen, it’s a matter of when. Because catastrophic events that seem like they’ll never happen will inevitably happen when enough time passes, it’s imperative to prepare against these scenarios even if they don’t seem “urgent.”

A typical losing strategy that most businesses do are:

This last big idea I got from Jim Collin’s Great By Choice is empirical creativity. It’s the idea that one should be creative when there’s underlying evidence to suggest that creativity would be useful.

That is to say: the most successful companies were generally innovative enough to be successful, but generally aren’t the most innovative.

He has an analogy in the book that he calls “Fire Bullets, Then Cannonballs.” It goes like this:

To be more clear: one should commit a lot of time/resource to an idea or direction only if it’s rigorously proven to work. This rigor can be achieved by observing/surveying the market, or through your own experiments (firing bullets).

One shouldn’t be innovative for the sake of it. Most of the companies that the book studied has shown that once you’ve passed a certain innovation threshold, more innovation doesn’t help the company in any way. Thus, the book isn’t saying you should have 0 innovation – it’s rather suggesting to innovate when you have the data to prove that it’ll work, and just do it enough to pass the threshold of prosperity.

Here’s how Amundsen and Scott approached innovation.

Amundsen approached innovation by using empirical data. He learned from Eskimos who are empirically proven to thrive even in extremely cold and harsh weather. He learned how to eat and move like Eskimos so that he’s at peak efficiency when he journeys down to the South Pole with his team. He also learned to use sled dogs because dogs are very good at keep warm. Dogs also never sweat which eliminates the possibility of their sweat turning into ice and killing them.

In short, Amundsen’s innovation is to copy Eskimos’ proven survival techniques.

Scott approached innovation differently. He was innovative in a more conventional manner.

He wanted to use engines to travel, because they’re faster. And he wanted to combine unproven engine technology with horses, because what’s faster than engines? Horses with engines! The engines failed early in their journey which quickly turned into a liability as they had to manually tow these heavy engines for the rest of their journey…until they died, of course. Their horses also died because their sweat froze over which killed them in the harsh Antarctic environment.

Amundsen learned from proven, empirical practices that’ll maximize his chances of surviving the harsh Antarctic environment. Scott was “too innovative” for his own good and got him and his team killed.

A lot of people read this and say “that’s not true! Apple is innovative and look how far they’ve gotten!”

But that’s a misconception.

A lot of people think of Apple as super creative when in fact they are the opposite in their prime. The iPhone isn’t new. It was based on the empirical evidence that people enjoyed the iPod and that people used Blackberries like crazy. Their touchscreen passed the innovation threshold, but the actual technology of iPod + internet on a device wasn’t innovative at all – it was just a combination of things that already existed.

And even today, they aren’t innovative at all. Apple normally waits a few years for new Android features to mature before deciding to do their own spin on it. This saves them from having to commit any resources if a popular Android feature is just a fad and never takes off.

There’s a few beliefs I have long held (and are also common beliefs in the entrepreneurial community) that this book’s busted.

Busting these myths is crucially important for me because it allows me to avoid wasting a ton of time going down the wrong paths in my own businesses.

For example, it busts the myth that innovation = success. While you need to have nonzero innovation and creativity to be successful, all creativity and innovation should be backed with empirical data. And nor should you be more innovative than necessary. This saves me a ton of time because I’ll know only to do “R&D” on something if there’s data to back up the effort. And I’ll know to not waste any extra time, effort, and money over-innovating as that’ll actually only increase risk and harm my business.

Another myth this book busts is that risk is correlated to success. It’s not. Looking at the Sharpe Ratio formula or thinking about “higher risk, higher reward” had me believe that taking more risk = more possibilities for extreme success. Nope. It turns out success comes from slower, but consistent execution. It doesn’t need to have a ton of risk.

You can go faster and take more risk. But the faster you drive, the easier you’ll get into accidents (and they’ll be more fatal, no less).

I feel like I can give myself permission to go slower, and be more consistent, as opposed to taking crazy risks after reading this book. Going down this path is a lot less stressful, and seems to be able to yield a lot more success anyway.

Great By Choice is a great book. It breaks down unintuitive lessons based on Collins’ immense empirical research.

The book also tells really good stories and draws parallels in Amundsen’s vs. Scott’s exciting South Pole expedition as it to entrepreneurship. The way that they tell the stories make the lessons much more memorable than if they were to explain the lessons in a much more dry and matter-of-fact way.

Having read 20+ books this year, I can say the well thought out structure of the book plus how the stories are presented makes this one of the most highly educational, yet entertaining read I’ve enjoyed this year.

In conclusion: 10/10 – definitely recommended for entrepreneurs because absorbing these lessons could mean life or death for your company. And if you’re not an entrepreneur, these lessons of being more prepared and not taking too much risk can be easily extrapolated to anyone’s career or personal finance journey.

My affiliate for the book link is here and I’ll get paid a tiny amount to keep this site running should you buy it, at no cost to you.