The past few years have highlighted the vulnerability of US supply chains, as well as the state of US infrastructure. In an event hosted by the Atlantic Council on June 23, 2021, National Economic Council Director BrianDeesehighlighted the United States’ need for “a new strategy[,] … an industrial strategy for the second quarter of the twenty-first century” that would strengthen US supply chains and promote climate resilience and equity through targeted public investment and public procurement. Encouraging Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), both inside the United States and abroad, must be central to such a government strategy, especially in sectors of strategic importance for the US economy, such as infrastructure and rare earth materials.

While US inbound and outbound FDI stocks have been growing over the past decade, they have shown signs of slowing down in the past few years.

As of 2019, the total US FDI in other economies (that is, outbound FDI position or stock) was around $6 trillion and foreign FDI inside the United States (US inbound FDI position or stock) stood at $4.5 trillion (see Figure 1), making the United States the largest recipient of FDI in the world. While the US inbound FDI stock almost doubled between 2010 and 2019, the US outbound FDI stock increased by 59 percent – pointing to the fact that in the past decade, foreign companies have been relatively more eager in establishing and expanding operations inside the United States than US companies have been in investing abroad. This is because besides being the largest economy in the world, the United States has continued to remain an innovative and stable market with a favorable business climate for foreign entities to operate in. However, global competition for FDI is increasing, and the United States needs to adapt swiftly to the changing FDI marketplace if it wants to continue to reap the benefits of being the leading destination of FDI in the world. In addition to contributing to the innovative base of the United States, inbound FDI has also benefited the US economy both in terms of job creation and exports promotion. For example, in 2018, the US affiliates of majority foreign-owned firms directly employed more than 7.8 million US workers and contributed around $400 billion to US goods exports. Moreover, every job created by an international firm supports three other jobs in the US economy, and 15 percent of all Research & Development (R&D) performed in the United States – equaling $67 billion – is conducted through foreign companies in the United States.

While the stock of FDI in the US economy has been growing over the past decade, the rate of inflows has slowed down in the past five years: declining from around $467 billion in 2015 to $134 billion in 2020. At the same time, since 2015 (except for 2017) the annual growth rates of the US outbound FDI position have on average been lower than the 2011-2014 period (Figure 2). The recent slowdown in US FDI, both inbound and outbound, could be because of the previous administration’s unilateral approach in many global issues, as well as its “America First” policy that deteriorated economic and commercial ties with many countries around the world, including traditional allies of the United States such as Canada and the European Union. Moreover, in 2020 and for the first time in recent history, China received more FDI than the US did: China’s FDI inflows were $163 billion, compared to $134 billion for the United States. While this development might be alarming, there are several reasons that could mitigate concerns, including the fact that the pandemic changed the global economy so dramatically in 2020 and pushed many trends out of equilibrium. Also, there is a possibility that the data revision for 2020, which will become available in a few months, would show a different picture. Moreover, China is lagging far behind the United States in terms of inbound FDI stock – around $1.9 trillion in China vs. $4.5 trillion in the United States. Nonetheless, the fact remains that the rate of annual FDI inflows into the US economy has been declining over the past five years – a decline of more than 71 percent between 2015 and 2020 – while annual FDI inflow into China has grown from around $136 billion in 2015 to $163 in 2020, an increase of 20 percent.

Also seen in Figure 2 is the contraction of the stock of US FDI abroad in 2018. This anomaly is an interesting case of the impact of corporate tax policies on FDI. Specifically, the US Tax Cut and Job Acts of 2017 (TCJA) shifted taxes towards a territorial tax model, hence exempting foreign profits from taxation in the United States. This resulted in US firms repatriating more than $776 billion in foreign profits, five times more than the average annual repatriation amounts in previous years going back to 2006.

Europe is the largest FDI partner of the United States, both for inbound and outbound FDI.

As shown in Table 1, in 2019, European firms were responsible for almost two-thirds of total FDI stock in the United States, followed by Japan and Canada at 13.9 and 11.1 percent, respectively. However, it is important to note that Europe’s share in the US inbound FDI stock has actually declined – from 72.8 to 64.4 percent during the 2010-2019 period – and this decline was mainly replaced by increases from Canada, Japan, and Latin America (see Table 1). Moving forward, it is imperative for the United States to maintain its current strong FDI ties with traditional allies, such as members of the G7 and other European economies. This is critical for two reasons. First, the United States needs to expand its partnership with allies to address their increasing risk and declining resiliency in the global supply chain of many strategic commodities. Second, while the Chinese FDI in the United States is minuscule and accounts for less than one percent of the total, it has grown by more than twelve times in the past decade, highlighting the eagerness of Chinese firms to establish their presence in the US market. That is even as the risk of US regulators taking aggressive actions against Chinese companies operating or listed in the US has increased in the past few years.

Not surprisingly, Europe has also been the most popular destination for US firms to invest in, with its share of US FDI abroad increasing from 54 to 60 percent between 2010 and 2019 (see Table 2). The Middle East has become more attractive for US companies to establish operations in, as the US FDI in this region has more than doubled since 2010. However, it is mainly limited to wealthy Persian Gulf economies. Africa was the only region that experienced a decline in FDI received from the United States, with the stock declining 21 percent between 2010 and 2019. While US firms have been leaving this strategic region, Beijing’s aggressive state-led industrial strategy and its support for investments abroad have encouraged Chinese firms to expand their presence in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). This has created serious supply chain risks in industries heavily dependent on minerals and metals that are primarily sourced from SSA, such as cobalt, which is an integral ingredient of large-capacity lithium-ion batteries widely used in electric vehicles (EVs) and the renewable energy industry.

State-backed investment in strategic industries must be part of a US FDI strategy for the remainder of the twenty-first century.

For decades, the United States was the main destination for foreign firms’ investments. Having the largest economy in the world, a large and wealthy consumer market, a culture of diversity and innovation, and access to deep capital markets and the world’s top talents have been some of the reasons for the attractiveness of the United States for foreign firms. However, the emergence of new markets and players in the global economy means the United States must actively compete with other countries – namely China – to maintain its appeal for foreign direct investment.

While it is too early to speculate, the recent slowdown of FDI into the United States and the slow but steady rise of FDI inflows into China might be the start of a long-run trend that could end with the United States losing its position as the largest recipient of FDI in the world. The recent trends could certainly be reversed in the coming years, as the new Biden administration is giving high priority to rebuilding the United States’ position in the international arena as a global leader and reestablishing strong economic and political ties with traditional US allies and others. At the same time, it is not clear if China will be able to maintain the upward trajectory of the past decade in attracting FDI, especially given the recent Chinese crackdown on Didi, which could cost China trillions of dollars in capital flows in the next decade.

Nonetheless, Chinas’ central role in global manufacturing and its dominance in the global supply chain of strategic industries such as large-capacity batteries and solar photovoltaic (PV) panels are important elements that could play in its favor to attract an increasing share of global FDI in the coming years and decades. For example, as of 2020, China was responsible for around 30 percent of global manufacturing output (vs. 18 percent for the US), more than two-thirds of all solar PV panels in the world (vs. 3 percent for the US), and more than 80 percent of the world’s total cobalt refining capacity (with practically none in the US). Moreover, Beijing’s state-backed outbound FDI has provided China with access to strategic commodities and markets. For example, in 2019, China’s FDI stock in the SSA region surpassed $110 billion, more than 2.5 times that of the United States. Most of these FDI positions are concentrated in key industries such as energy, metals, mining, and transportation, which have strengthened China’s supply chain and resilience in strategic commodities.

Considering the growing presence of China – and that of other emerging economies – in the global FDI marketplace, the US government must consider taking a more active role in this front. Specifically, the US needs to incentivize inbound and outbound FDI in strategic sectors and regions of the world, especially where China is expanding rapidly through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and other state-financed development projects. Not doing so risks creating instabilities in the US supply chain and allowing China to potentially disrupt US industries.

For example, the mining sector in SSA is heavily dominated by Chinese companies, and cobalt is a particularly illustrative case. According to the US Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy, cobalt has the highest material supply chain risk for lithium-ion batteries and EVs in the United States. The strategic importance of cobalt and other critical materials needed for lithium-ion batteries for the US economy is highlighted in a recent White House report on supply chain resilience, one-fourth of which is dedicated to Large Capacity Batteries. Referring to China’s “Going Out” FDI policy, the report warns that through state-led and -supported FDI, Chinese firms have dominated the global cobalt mining and refining industry, which is mainly concentrated in a few SSA economies such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Zambia. Home to approximately 80 percent of the world’s known cobalt reserves and accounting for more than 40 percent of global cobalt ore exports, the DRC remains the largest player in the global cobalt market. While China’s presence in the DRC’s cobalt mining industry has been increasing – with 40-50 percent Chinese ownership – the United States has been widely absent, risking the long-term resilience of US industries that are dependent on lithium-ion batteries, specifically the EV and renewable energy industries which will be increasingly important as momentum builds to make the US economy greener.

Considering the substantial involvement of the Chinese state in supporting FDI abroad, US firms who lack government support are not able to compete with the state-backed Chinese firms who are investing heavily in the energy, transport, real estate, minerals, and metals sectors in SSA, the Middle East and North Africa, and elsewhere. This is one reason why the US FDI stock in SSA contracted by 21 percent in the last decade while Chinese investment in the region expanded rapidly. Therefore, in the absence of a government-led industrial strategy and state-backed targeted FDI in strategic SSA economies, US manufacturing – especially the EV and renewable energy industries – will continue to face serious supply chain risks and vulnerabilities. Given that large capacity batteries are central to some of the components of the recent infrastructure agreement that was reached between the White House and the Senate, it is not inconceivable that the federal government might also allocate funding – as part of the infrastructure spending – to secure a reliable supply base of rare earth materials needed for lithium-ion as well as next-generation batteries. Achieving this objective, as the report correctly recommends, requires the United States to work closely with its allies and partners to increase the production of batteries and ensure reliable access to the necessary raw and refined materials. The recent Build Back Better World (B3W) initiative, which was launched by President Biden and G7 leaders in the latest G7 meetings in June 2021, could act as a platform for such future collaborations between the United States, EU, and other allies, encouraging targeted international investment and strategic FDI in SSA economies that are rich in mineral and earth materials.

The same strategy could be applied to other areas highlighted in the infrastructure bill, such as roads, bridges, highway safety, renewable energy, electric vehicle charging stations, rapid rail, and drinking and wastewater infrastructure, where the United States could encourage targeted investment in foreign firms and industries supplying materials as well as technologies and expertise needed to revitalize US infrastructure in these areas. As a result, in addition to boosting the US economy in the short-run and safeguarding its wellbeing and resilience in the long run, US infrastructure spending could also increase US FDI in allied and other strategic economies.

Moreover, US infrastructure could benefit substantially from inbound FDI in this sector. According to a report completed by the Council on Foreign Relations in April 2021, “US infrastructure is both dangerously overstretched and lagging behind that of its economic competitors, particularly China” and is costing the US economy hundreds of billions of dollars each year as well as putting citizens’ lives at risk. In 2002, the United States ranked fifth in the world in terms of infrastructure quality. By 2019, that ranking had dropped to thirteenth. Many countries in Europe, Asia, and even the Middle East are ahead of the United States when it comes to modern infrastructure such as smart cities, high-speed rail, eco-friendly buildings, smart grids, and e-government. The failure of the power grid in Texas because of a severe winter storm in February 2021 and the ransomware attack on the Colonial pipeline in May 2021 are recent examples of serious vulnerabilities in US infrastructure.

The same is true for non-traditional infrastructure, such as the semiconductor industry, which is as fundamental to the workings of an economy as traditional infrastructure. The recent shortage of semiconductors was a wake-up call for the US economy as US policymakers realized around 75 percent of the world’s semiconductor production is taking place in China and a few other economies in East Asia. Furthermore, more than 90 percent of the world’s most advanced semiconductor capacity is located in one economy – Taiwan – whose sovereignty is frequently threatened by China. This has encouraged the European Union and the United States to seriously contemplate expanding their semiconductor manufacturing capacities. A report by Boston Consulting Group highlights the need for government incentives to promote private investments in the semiconductor industry. The report estimates that $50 billion in government-funded incentive programs over the next ten years would be a good starting point for the US government to gradually reestablish the United States “as an attractive location for advanced semiconductor manufacturing”.

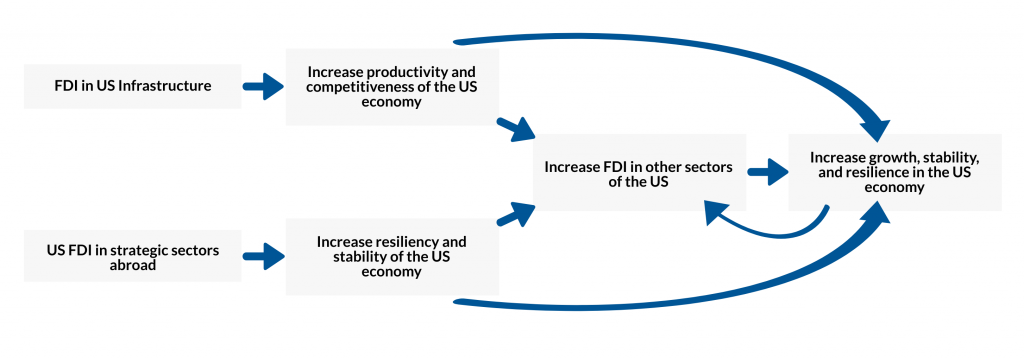

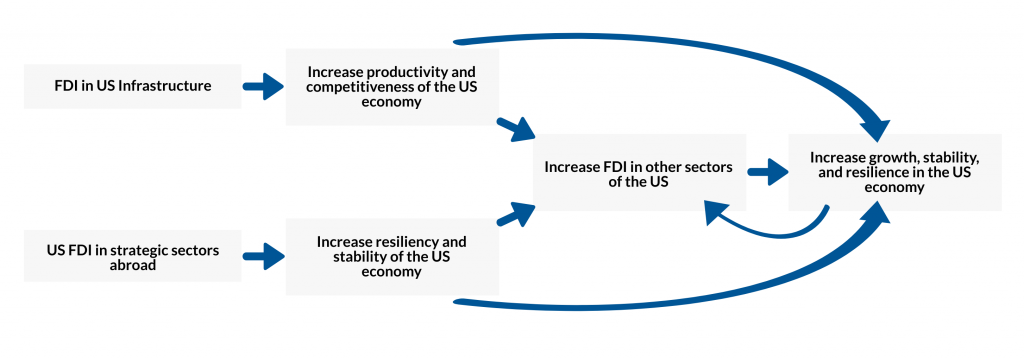

However, the United States is not able to meet the current financing and technological gap solely through domestic private and public investment schemes. Therefore, it is imperative for the US to incentivize greenfield and brownfield FDI in US infrastructure – traditional and non-traditional – to improve its quality and resilience in the face of the growing frequency of adverse events and vulnerabilities. This will in turn increase the productivity, efficiency, and competitiveness of the US economy, contributing to its sustained appeal as a leading FDI destination in the second quarter of the twenty-first century.

To conclude, there is no doubt that the wellbeing of the US economy in the 21 st century and beyond will depend greatly on a new industrial strategy through which the United States – with the help of its allies – could strengthen its strategic supply chains and resilience. This is because, in the words of Director Deese, “the idea of an open, free-market global economy ignores the reality that China and other countries are playing by a different set of rules. Strategic public investment to shelter and grow champion industries is a reality of the twenty-first-century economy. We cannot ignore or wish this away. That’s why we need a new strategy.” Clearly, such a strategy will require the US government to encourage investments in strategic sectors – both in the US and abroad – where long-term supply chain redundancies could be established. Advanced semiconductors and strategic minerals and metals are two obvious sectors, and Sub-Saharan Africa is an obvious region for the United States to seriously consider increasing investments in. It is time to go back to the drawing table and identify more sectors and countries that are crucial to US supply chains for the United States to actively promote investments in. After all, industrial policy and state-backed strategic FDI are undeniable realities of the twenty-first century.